Our immune system has a dark side: It’s supposed to fight off invaders to keep us healthy. But sometimes it turns traitor and attacks our own cells and tissues.

What are called autoimmune diseases can affect just about every part of the body – and tens of millions of people. While most common in women, these diseases can strike anyone, adults or children, and they’re on the rise.

New research is raising the prospect of treatments that might do more than tamp down symptoms. Dozens of clinical trials are testing ways to reprogram an immune system-gone-rogue, with some promising early successes against lupus, myositis and certain other illnesses. Other researchers are hunting ways to at least delay brewing autoimmune diseases, spurred by a drug that can buy some time before people show symptoms of Type 1 diabetes.

“This is probably the most exciting time that we’ve ever had to be in autoimmunity,” said Dr. Amit Saxena, a rheumatologist at NYU Langone Health.

Here are some things to know.

They’re chronic diseases that can range from mild to life-threatening, more than 100 with different names depending on how and where they do damage. Rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis attack joints. Sjögren’s disease is known for dry eyes and mouth. Myositis and myasthenia gravis weaken muscles in different ways, the latter by attacking how nerves signal them. Lupus has widely varied symptoms including a butterfly-shaped facial rash, joint and muscle pain, fevers and damage to the kidneys, lungs and heart.

They’re also capricious: Even patients faring well for long periods can suddenly have a “flare” for no apparent reason.

Many start with vague symptoms that come and go or mimic other illnesses. Many also have overlapping symptoms – rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s also can harm major organs, for example.

Diagnosis can take multiple tests, including some blood tests to detect antibodies that mistakenly latch onto healthy tissue. It usually centers on symptoms and involves ruling out other causes. Depending on the disease it can take years and seeing multiple doctors before one puts the clues together. There are efforts to improve: The National MS Society is educating doctors about newly updated guidelines to streamline diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

The human immune system is a complex army with sentinels to detect threats like germs or cancer cells, a variety of soldiers to attack them, and peacemakers to calm things down once the danger is over. Key is that it can distinguish what’s foreign from what’s “you,” what scientists call tolerance.

Sometimes confused immune cells or antibodies slip through, or the peacemakers can’t calm things down after a battle. If the system can’t spot and fix the problem, autoimmune diseases gradually develop.

Most autoimmune diseases, especially in adults, aren’t caused by a specific gene defect. Instead, a variety of genes that affect immune functions can make people susceptible. Scientists say it then takes some “environmental” trigger, such as an infection, smoking or pollutants, to set the disease into motion. For example, the Epstein-Barr virus is linked to MS.

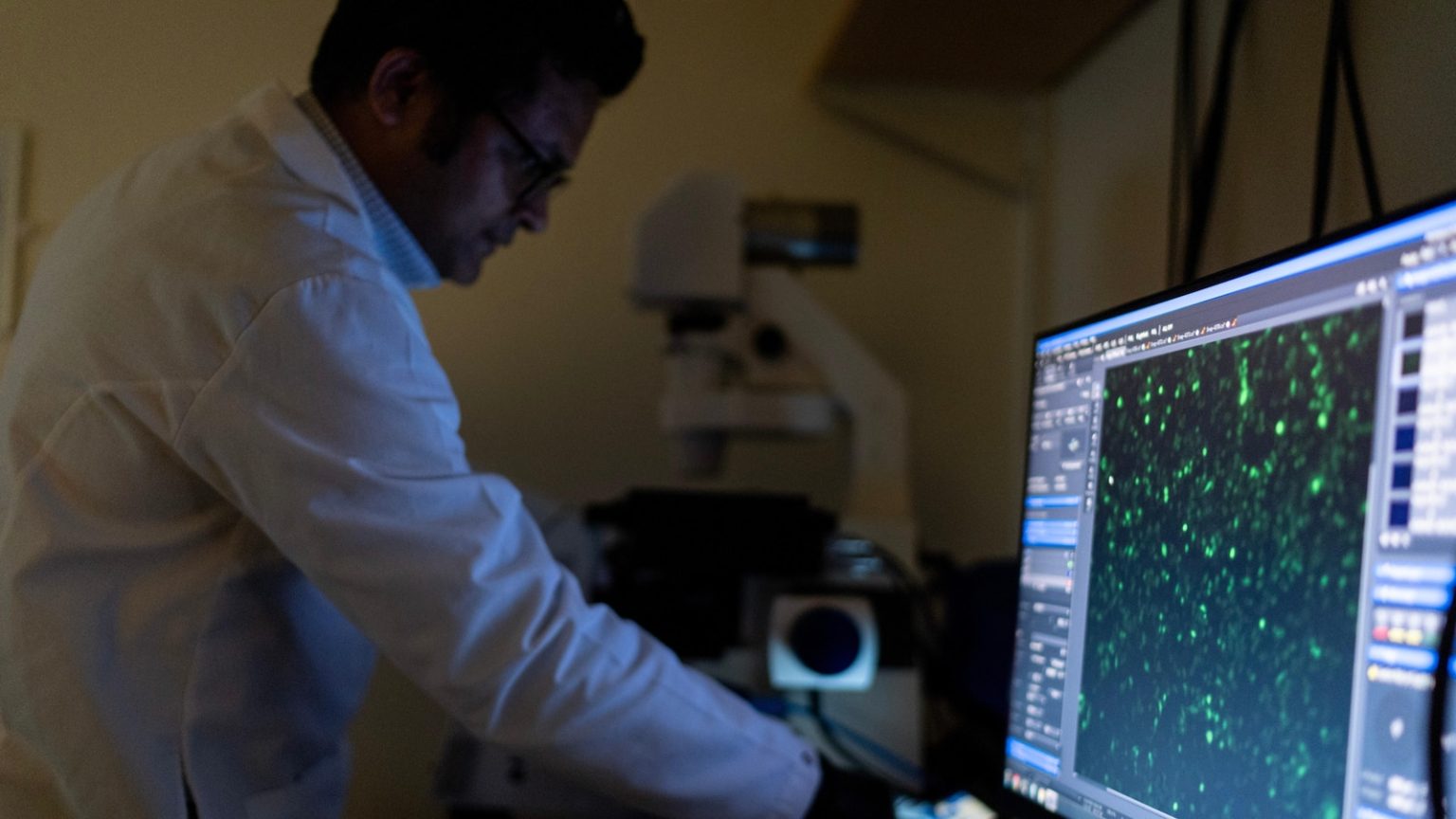

Scientists are zeroing in on the earliest molecular triggers. For example, white blood cells called neutrophils are first responders to signs of infection or injury — but abnormally overactive ones are suspected of playing a key role in lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases.

Women account for about 4 of 5 autoimmune patients, many of them young. Hormones are thought to play a role. But also, females have two X chromosomes while males have one X and one Y. Some research suggests an abnormality in how female cells switch off that extra X can increase women’s vulnerability.

But men do suffer from autoimmune diseases. One especially severe one named VEXAS syndrome wasn’t discovered until 2020. It mainly affects men over 50 and in addition to typical autoimmune symptoms it can cause blood clots, shortness of breath and night sweats.

Certain populations also have higher risks. For example, lupus is more common in Black and Hispanic women. Northern Europeans have a higher risk of MS than other groups.

According to investment research company Morningstar, the global market for autoimmune disease treatments is $100 billion a year. That’s not counting doctor visits and such things as lost time at work. Treatment is lifelong and, while usually covered by insurance, can be pricey.

Not so long ago there was little to offer for many autoimmune diseases beyond high-dose steroids and broad immune-suppressing drugs, with side effects that include a risk of infections and cancer. Today some newer options target specific molecules, somewhat less immune dampening. But for many autoimmune diseases, treatment is trial and error, with little to guide patient decisions.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.