[SINGAPORE] Carrie (not her real name) can still clearly remember her trauma from 20 years ago. What was meant to be a short detour to a hiring manager’s home to pick up a few items ended up in a traumatic act of sexual violence.

He had offered her a ride to her night classes, after their third meeting during a job interview process. What transpired left the then 20-year-old so overwhelmed by shock, fear and self-blame that she reported the incident three days later.

Instead of receiving support, she was met with doubt.

More than a month ago, the former vice-president of The Law Society of Singapore (LawSoc), Chia Boon Teck, sparked public outcry over comments he made on a rape case involving TikTok personality Lev Panfilov, who was convicted by the High Court of raping a woman he met on dating app Tinder.

BT in your inbox

Start and end each day with the latest news stories and analyses delivered straight to your inbox.

Chia had said in a LinkedIn post – before deleting it shortly after the uproar – that “people who indulge in one-night stands may wanna take note to protect themselves from attack, or accusations of attack”.

He also added, among other things, that the victim was “not exactly a babe in the woods” given her age and her occupation as an actress and model.

Besides receiving backlash from his peers in the legal fraternity, Chia also drew sharp rebuke from Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam, who raised concerns that his position as LawSoc vice-president might cause people to “think that the views he has expressed indicate the norms in Singapore”.

SEE ALSO

Chia eventually resigned from his vice-president position after calls from the society’s president to do so.

For all of Singapore’s progress, instances of victim-blaming still linger, suggesting that societal attitudes may have yet to catch up. What more can be done to dismantle archaic mindsets and enact real change?

Silenced and gaslit

Victim-blaming has wide-ranging negative impacts on sexual assault survivors, often causing them to be shamed, re-traumatised and silenced, says Sugidha Nithiananthan, director of advocacy and research at the Association of Women for Action and Research (Aware), a non-profit organisation that advocates for gender equality and provides critical support services for women in Singapore.

The problem is compounded when such comments come from professionals whom sexual assault survivors are meant to trust.

Whether from lawyers, law enforcement officers or healthcare workers, victim-blaming language from these individuals lends legitimacy to the view that sexual assault survivors are, somehow, at fault, says Stefanie Yuen Thio, who is joint managing partner at TSMP Law.

“More importantly, these are the people that victims seek help from, so the betrayal of trust is even greater. Survivors of sexual assault (are already dealing) with a plethora of traumatic emotions and it is more difficult for them to report a sexual crime than an offence of a different nature. Victim-blaming attitudes will be a huge disincentive for them to come forward,” adds Yuen Thio, who is also chairperson of SG Her Empowerment, a non-profit focused on tackling women’s issues.

Nithiananthan says that it is common to hear from sexual assault survivors, who sought assistance at Aware’s help centre, hesitating to report their abuse due to fears of judgment or not being believed. “Sadly, some of these fears are realised when they encounter re-traumatising responses from the police or in court.”

For Carrie, the insinuations made at the time led her to doubt her own memory of the assault.

“Because if other people can’t see it, is it just me? Am I really making things (up in) my head? But I’m very clear about what I went through. But why is it that when I tell people, no one believes me?” she says.

The lack of a supportive environment can also become a barrier to the healing journey of sexual assault survivors.

When Sharon (not her real name) told her industry peers that she was violated by the chief editor of a magazine where she was freelancing, the reactions she received ranged between nonchalance, at best, and doubt, at worst.

As a young beginner eager for the opportunity to write for the magazine, what was meant to be a photo shoot for her professional headshots turned exploitative when she was pressured to pose in compromising positions wearing only her lingerie. The then 21-year-old ended up being sexually assaulted during the photo shoot.

Her peers’ reactions afterwards made her feel small, she says, and made her want to withdraw more into her shell and not talk about what had happened. “Here I am trying to share something very personal, and obviously I’m looking for support,” says the marketing professional, who is now 39 years old.

“I think the reason why I spoke to these people was because they knew (the chief editor). I don’t know whether I was hoping for some kind of justice or advice on what to do. But not a single person told me to take it up with his boss,” she adds.

Nithiananthan says that underlying this pervasive culture of victim-blaming are rape myths, which refer to false beliefs that focus on and lay the blame on the survivors of the sexual assault, instead of on the perpetrators.

“At the heart of rape myths lie gender stereotypes and patriarchal norms that prioritise male perspectives and cast doubt on women’s experiences. Even educated and respected members of society and people in positions of authority, who would be expected to know better, can internalise these perceptions without recognising them,” she adds.

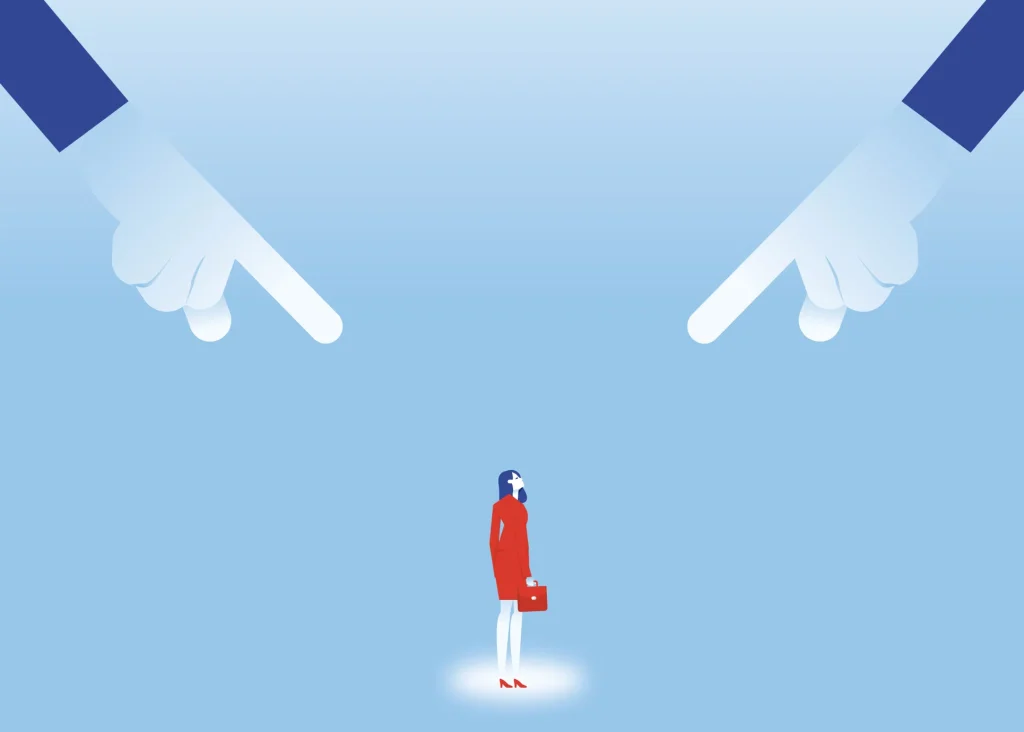

Unequal power dynamics

A common thread running through almost all sexual assault or harassment incidents is the unequal power dynamics between the victim and perpetrator.

And such dynamics are uniquely fraught when the sexual assault takes place in a workplace environment, given the layer of institutional protection that companies may provide to the perpetrator.

“Survivors may fear retaliation, stalled career progression, or reputational damage, especially when the perpetrator holds a position of influence,” says Nithiananthan.

“In such environments, victim-blaming can become structural: a means for organisations to minimise liability and preserve reputations, rather than centring (on) the survivor’s well-being and safety.”

It is precisely this fear that prevented Sharon from coming forward almost 20 years ago.

“(I was) worried that I (would) lose job opportunities. And then, what if people (didn’t) believe me? Because you’re talking about a 50-year-old man versus a 21-year-old… He has so much credibility in the industry. I (was) new, (was) trying to break into this industry,” she adds. At the time, she felt she would “rather take the path of least resistance and not do anything”.

Unfortunately, though there has been some progress, gender equality advocates believe that corporations in Singapore are still not adequately equipped to handle sexual assault incidents at the workplace in a sensitive manner.

Sexual assault survivors who have reached out to Aware’s help centre often recount how their experiences were dismissed, minimised or ignored, says Nithiananthan.

Many human resources departments continue to lack the training, resources, and independence to respond effectively. Some organisations do not even have clear reporting channels, confidential processes, or any policies in place at all.

Their instinct is often to protect the company or a high-performing employee rather than support the survivor, she adds.

Yuen Thio notes: “I’ve heard too many stories of how human resources departments tried to sweep the complaint under the table, even apparently trying to be kind by explaining how a complaint would make the complainant look bad.”

Of course, unequal power dynamics do not just exist in a workplace environment.

Rachel, who declined to give her full name, did not realise she was being groomed when she entered into a relationship when she was 15 years old with her church’s cell group leader who was almost a decade older than her.

Naturally, she also did not have the language to articulate that the sexual acts she had with her then boyfriend were non-consensual, and were therefore sexual assaults.

“There were people at church who knew that this older guy had sex with me. Nobody ever flagged that (what he did) was inappropriate. The thing that was flagged (as) inappropriate was me having sex. A lot of it was (church) leaders trying to correct my so-called lack of purity,” says Rachel, who is now a 31-year-old communications professional.

What more can be done?

Legislations and court processes have been introduced in Singapore to address the problem of victim-blaming at workplaces and in the criminal justice system.

The Workplace Fairness Act was passed in January 2025 to protect against discriminatory behaviours based on several characteristics, including sex. While sexual assault or harassment is not explicitly addressed in the legislation – as there are other laws in place that criminalise such behaviour – it mandates employers to implement processes to address harassment complaints, including sexual harassment.

However, adapting to significant legislative changes can vary widely depending on several factors, including the size of the organisation, existing workplace culture, and the resources available for implementing changes, says Susan Fanning, head of well-being solutions for Asia-Pacific at professional services firm Aon.

“During this adaptation process some organisations may still struggle with deeply ingrained biases and inadequate policies,” she adds.

Besides legislation, the judiciary has also taken major steps towards addressing this problem by having judges undertake active case management of sexual assault cases before it goes to trial. They also have to adopt a two-step framework to ensure that all questions during the cross-examination of a sexual assault survivor are relevant and appropriate, says Nithiananthan.

Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon stated in December last year that the process of cross-examination in sexual offence trials should be handled with more care and sensitivity.

He highlighted how a line of questioning pertaining to why victims did not seek help immediately after they were assaulted may not be allowed in particular cases, as it assumes that victims of sexual offences would make immediate reports and/or react in a uniform way.

Nonetheless, Aware believes that there is still a need for more policy reforms in Singapore, including having broader protections for survivors of sexual violence, legislation to address tech-facilitated sexual abuse, as well as implementing trauma-informed training and processes throughout the criminal justice system.

Yuen Thio, however, thinks that what is needed is a shift in gender mindsets, instead of having more government policies or campaigns on the specific issue of victim-blaming.

In the corporate sphere, observers note that there is still plenty of room for improvement in how corporations here manage sexual assault or harassment incidents.

In addition to setting up accessible reporting mechanisms and training human resources managers to handle complaints, having comprehensive anti-harassment policies, appointing external parties for complex cases, as well as ensuring that the perpetrators are held accountable were also highlighted.

“This approach not only helps in addressing harassment effectively, but also promotes a healthier, more supportive work environment where all employees feel valued and safe,” notes Fanning.

Yuen Thio adds that that having the complaint process published to employees would provide assurances of confidentiality and how their complaint will be dealt with and by whom.

“The process must ensure transparent accountability, enforced by someone or a body of persons with the relevant seniority in the organisation,” she adds.

Stronger institutional support might have made the difference for Carrie and Sharon back then, both of whom expressed regret for not pursuing further action against their perpetrators.

“If there was a strong enough mentor who (had) told me, ‘Look, this is not right at all. He shouldn’t be doing this to you’, and (told) me what I could do… If there was someone who (had given) me that assurance and that guidance, I think I would have actually done something,” says Sharon.