The concept of rebirth is central to Buddhism, which teaches that every individual has more than one life. That also appears to be true of the Rubin Museum of Art, long one of New York City’s prime locations for viewing Buddhist works. Although the institution closed its doors permanently in October 2024, one of its most cherished installations is taking on a new existence: The Rubin Museum Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room will reopen on Wednesday for a six-year stay at the Brooklyn Museum.

The Shrine Room, which Holland Cotter, the chief art critic of The New York Times, once described as “magnificent,” is now on the Brooklyn Museum’s second floor, in its Arts of Asia Galleries, where it is like a darker jewel wedged among a series of modernist white boxes. Carefully reassembled to incorporate the same wooden posts and overhead beams as at the Rubin, the 400-square-foot enclosed space also includes the original’s transparent glass doors, which both welcome in onlookers and gently seal them off from exterior noise.

“We didn’t want the Shrine Room to be a thoroughfare,” Joan Cummins, the Brooklyn Museum’s senior curator of Asian art, said in an interview at the site.

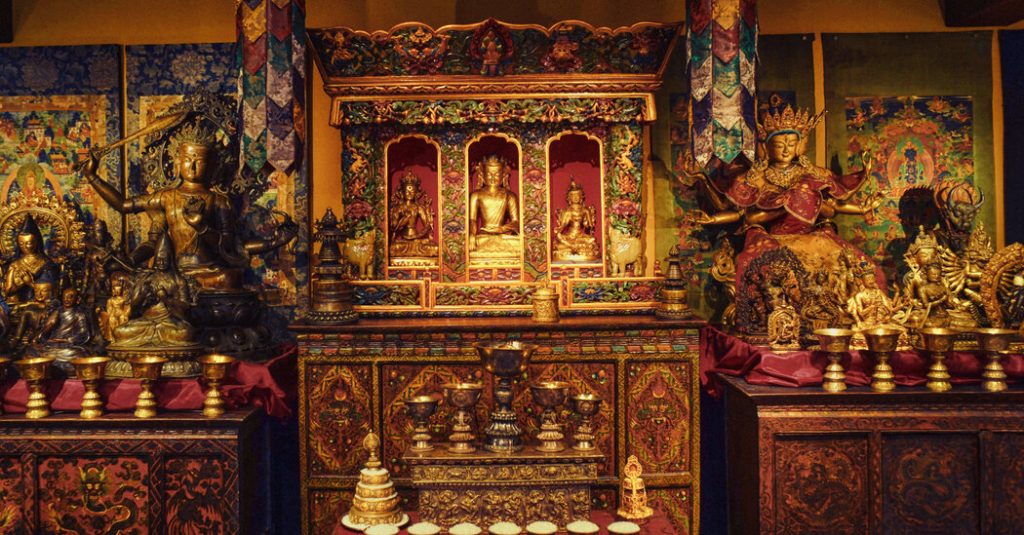

Inside, the space looks as if it had been dropped in intact from a prosperous Tibetan home, featuring colorful thangkas, or scroll paintings, as well as elaborate decorations to welcome gods. Silver offering bowls and statues of deities in various metals sit atop painted furnishings, along with musical instruments — an elegant bell, a conch shell repurposed as a trumpet, Mongolian cymbals attached to flowing silk.

The faint scent of incense fills the air, along with the recorded chants of Buddhist monks and nuns. The Shrine Room invites visitors not just to gaze on more than 100 artifacts from nine centuries but also to sit on small stools and experience the space as a Tibetan family might: as a place for meditation or prayer, as a refuge from a fractious world.

“Standing in front of objects in something that was reminiscent of their original context is a very, very powerful experience,” Jorrit Britschgi, the Rubin’s executive director, said in a telephone interview.

Seeking to ensure the Rubin’s long-term stability, its leaders said in a statement last year that they were redefining the 21-year-old institution as a “global museum” without walls. Now called the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, it has retained its collection and continues to lend its treasures and organize traveling shows.

The Shrine Room is its first major installation in New York since its Manhattan building closed. The museum’s leaders considered it especially important to find this exhibition a temporary local home: Since it opened at the Rubin in 2013, the Shrine Room has welcomed more than a million visitors, including devotees like the actor Michael Imperioli, the artist Laurie Anderson and the musician Moby, as well as legions of typical New Yorkers.

“There was one woman in particular who would come every day when the museum was open,” Elena Pakhoutova, the Shrine Room’s curator and a senior curator of Himalayan art at the Rubin, said in an interview. Around 11 a.m., this visitor would appear, go directly to the Shrine Room, sit there for 15 minutes and then leave. “That was her practice,” Pakhoutova said.

An even wider public may flock to the space after its relocation and reopening, which were carefully selected: This year, June 11 is Saga Dawa Duchen, which in Tibetan culture marks the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and death. The Rubin chose the Brooklyn Museum for its large, diverse audience and its on-site admissions policy — pay what you can — which ensures the Shrine Room’s accessibility.

“We’re going to have a lot of people who discover the Shrine Room by accident,” Cummins, the Brooklyn curator, said. “And I think that’s going to be kind of magical for a lot of them — to run across this room where art is displayed in such an immersive way that is so different from how we show art in the adjacent spaces.”

As in its original location, the room has no labels. The Brooklyn Museum has stationed a large touch screen outside, where visitors can tap on the objects in an image of the Shrine Room to learn about their history — a virtual exploration that is on the museum’s website as well.

But the reincarnated Shrine Room also differs from the original. Because of space constraints, two of its most imposing pieces, the richly painted wooden Wrathful Shrine Doors, thought to have come from a small 19th-century Tibetan shrine dedicated to the fierce protector god Mahakala — he stares from their surface — now sit just outside the room.

It also has transformations within. The Rubin rotated the room’s objects — almost all come from its own collection — every two years to reflect each of Tibetan Buddhism’s four main traditions, a practice the Brooklyn Museum will continue. At the time the Rubin closed, the Shrine Room featured the Kagyu tradition. Now it embodies the more recent Geluk tradition, and all of its thangkas and about half of its sculptures have been replaced.

Geluk is “known for its learning and scholarship,” Pakhoutova said. The room’s pieces that are now going on view for the first time since 2015 include a 20th-century metalwork statue portraying Tsongkhapa, the tradition’s 14th-century founder, as well as an 1800s silk brocade thangka depicting Tara, a female Buddha.

“She tends to be someone that you pray to for sort of worldly worries, long life, health,” Cummins said.

Being among such objects can’t help impressing visitors who wander in, she observed.

“It is transporting,” Cummins said. “It’s like stepping into Tibet for a moment.”