Outside the apartment, our situation was less predictable. As I strapped my son to my chest in a carrier and walked him around the city, his very first encounters with strangers were charged. His tongue usually rested outside his mouth, and they sometimes interpreted this as a provocation. People stuck their tongues out at him, then laughed in confusion when he didn’t pull his back in. They yelled after us as we walked away, hooting about the tongue’s size. They approached him in the park or drugstore and said, “Whoa!” or “Is he sick?” When I slipped his passport application under a slot at the post office, a worker gruffly pushed it back, saying that the government would not accept a photograph of a child doing that with his tongue. I buzzed with rage at these encounters, and the helplessness they exposed in me. I felt unfit for the task of representing my son to the world. I needed to work out how to embrace his BWS while preparing for the distress that it could cause.

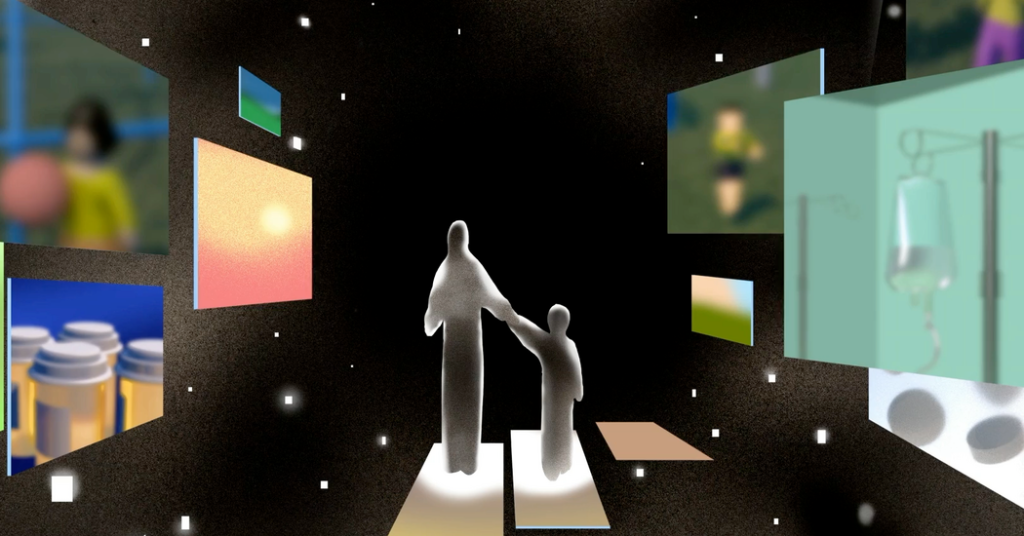

A pediatrician whom Marc contacted suggested that we consider joining a parent-support group. I searched for them on Facebook and requested access right away. When they unlocked their doors, I slipped inside gratefully. Just the size of the groups — they had thousands of members — steadied me. Parents shared stories, concerns and photos of their children, in sickness and in health. The groups were not straightforwardly reassuring. Often they coursed with uncertainty and pain. But they were comforting in a deeper way, in how they allowed me to redistribute the burdens of my private worries.

The parents in the BWS groups told stories about how their children were perceived. Every ignorant comment could be inscribed into our secret book: the pediatrician at an appointment who said, “She might not go to Harvard”; the grandmother at the aquarium who said, “That baby looks retarded.” Every word felt torpedoed straight at my son. I had encountered the word “retarded” only infrequently since junior high school, but now it seemed to follow me around. Most children with BWS did not have intellectual disabilities, but some other children with large tongues, such as those with Down syndrome, did. The grandmother at the aquarium had said: “Oh, sorry you heard me, but your Down-syndrome baby is cute — you know that.” A big tongue was a minor human variation, but the slur was a blunt reminder of the punishment exacted on anyone suspected of difference.

Though BWS was rare, the world of social influence was vast enough that I found a handful of accounts where parents posted about children who had it. I followed them and watched them act out our new life in the form of a burlesque. I wasn’t interested in broadcasting our family this intentionally, but I also knew that we would be on view whether I liked it or not. I looked to these BWS influencers for clues about the messages I might send, perhaps without quite realizing it. A parent who baked apocalypse-themed treats danced while gesticulating to their daughter’s symptoms in floating text bubbles, performing the blasé normalcy of the condition even as they explained it at length. The father of an extreme-couponing family, who bought items on clearance and resold them on eBay and Amazon, pitched his fourth child’s BWS as a kind of motivational project. The diagnosis, he said in a video titled “Never Give Up!!,” set them “on the path to couponing,” and their son’s extended hospital stay did not stop them. “We bought more stuff,” he wrote. “We couponed harder.”

I followed a Pennsylvania mother who posted on TikTok under the name @largerthanbws, and I watched a video she published under the trending prompt “Show your baby as a newborn vs. now.” It opened with a shot of a big-cheeked newborn baby, sleeping in a lap, sucking on his own big tongue as if it were a natural pacifier, just as my son did. Then — pop! — he became a mop-haired little boy with a toothy smile. In this TikTok trend, the videos with the most dramatic transformations traveled further on the app, and this one had been viewed more than four million times. I picked through the comments that stuck to it like old chewing gum. There were heart emojis, laugh emojis, skull emojis. Some expressed confusion, asking why these images had confronted them in their feeds. One person said: “I’d send it back.”